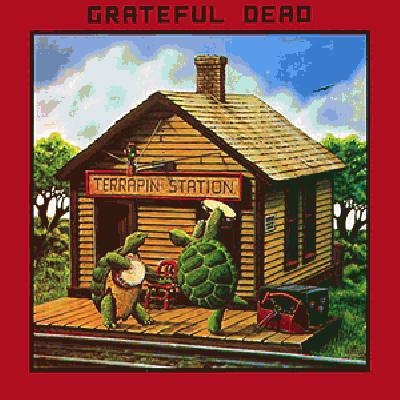

Music producer Keith Olsen’s resume looks like a who’s who of mainstream rock artists from the 1970s and 1980s, including Fleetwood Mac, Rick Springfield, Ozzy Osbourne, Europe, Whitesnake, Bad Company and Joe Walsh, among others. His work also appeared on soundtracks for such iconic films as Top Gun, Footloose, Flashdance and Vision Quest. Before the 80s hit full blast, Olsen also produced the Grateful Dead’s ninth studio album Terrapin Station in 1977. In true Grateful Dead fashion, the album failed to set the charts on fire, and it contains some of the band’s most interesting studio tracks, and at least one of their worst.

A band like the Dead hiring someone like Olsen may seem a bit odd in retrospect, like if Phish or Wilco suddenly flew to Sweden to work with Max Martin. But in 1977, the Dead were in a bit of career funk. Ten years removed from their Haight-Ashbury heyday, the band’s business was in trouble. Their label, Grateful Dead Records, had recently folded after the release of Blues for Allah due to bad management and disappointing sales. This led them to sign with Arista Records. When the label’s founder Clive Davis brought the band into his stable of artists, one of his many demands was that they hire an outside producer to make them more palatable to mainstream radio. The band had self-produced its last few albums with uneven results.

To handle such a daunting task, Davis handpicked Olsen, who had recently scored his major breakthrough by producing Fleetwood Mac’s self-titled 1975 album, which contained such hits as “Rhiannon” and “Landslide.” Olsen was a true neophyte to the Grateful Dead’s music. “I didn’t know their records. I was as far away from what they did as possible.” Before taking on the band, he listened to some of their records and thought, “How am I going to fix this?”

When the project began, Olsen forced the group to rehearse extensively in their Front Street studio in San Francisco before bringing them down to Los Angeles for the actual recording sessions. “Keith was cracking the whip, but we liked it,” Mickey Hart said. “It made us sharper. We became much more disciplined. We were trying to make a real record, for Clive.” Once recording started, Olsen was less than impressed by his new charges working habits. David Browne writes that “25 percent of [Olsen’s] time was devoted to rounding up the band: just when a few of them were ready to get to work, others would wander off. And even when he managed to get them together, they didn’t always stay in the same room for very long.”

Despite Olsen’s concerns, the efforts clearly paid off as the album is bookended by two Dead classics, the opening and closing tracks “Estimated Prophet” and “Terrapin Station.” Olsen’s studio wizardry is all over both of the songs, to the delight of some band members and the downright outrage of others.

The opener, “Estimated Prophet” is the band’s ode to their home state of California, depicted in the chorus as an Eden-like paradise:

California, a prophet on the burning shore

California, I'll be knocking on the golden door

Like an angel, standing in a shaft of light

Rising up to paradise, I know I'm gonna shine.

California, I'll be knocking on the golden door

Like an angel, standing in a shaft of light

Rising up to paradise, I know I'm gonna shine.

That vision presents a stark contrast to the more somber tale in the song’s verses, where Bob Weir is constantly reminding the listener that: “My time coming, anyday, don't worry about me, no.”

Weir claims the song, which he co-wrote with John Perry Barlow, is his personal reaction to the adulation he received from fans. “Every time we play anywhere there’s always some guy that’s taken a lot of dope and he’s really bug-eyed and he’s having some kind of vision. Somehow I work into his vision … So I guess I just decided I was going to beat him to the punch and do it myself. I’ve been in that space and I know where’s he’s coming from. If there’s a point to ‘Estimated Prophet’ it’s that no matter what you do, perhaps you shouldn’t take it all that seriously.”

The music itself has a decidedly West Coast (aka Yacht Rock) feel. This is thanks in part to the sax solo, performed by fusion jazz musician Tom Scott, who was brought in by Olsen. While other members of the band would ultimately be dismayed by some of Olsen’s constant tweaking of the process, Weir was happy with the final result. “As it is, I’m kind of pleased overall with what [Olsen] did on ‘’Estimated Prophet’ — it’s not often I heard one of my tunes all dressed up like that.” Weir would subsequently hire Olsen to produce his 1978 solo record Heaven Help the Fool.

The album closes with “Terrapin Station,” sometimes known as “Terrapin Station Part 1,” the Dead’s sprawling 16-minute masterpiece. The band was no stranger to long-form, multi-track suites on its albums. Previous extended efforts included, “That’s It For the Other One” on Anthem of the Sun, “Weather Report Suite” on Wake of the Flood and the notoriously awful title track to Blues for Allah, all of which contained several different movements. But unlike those tracks, which are very jammy, “Terrapin Station” is a tighter and more calculated work, similar to epic prog rock pieces of the era, like Styx’s “Movement for the Common Man,” Rush’s “2112,” or Genesis’ “Supper’s Ready.” The work is so complex the band would never play it live in its entirety.

The song opens with “Lady with a Fan,” a ballad similar to the old standard, “Lady of Carlisle.” The lyrics then delve into an exploration of “Terrapin,” an ethereal destination not all that different from the depiction of California on “Estimated Prophet.” “Some rise/Some fall/Some climb/To get to Terrapin.” The suite then proceeds into a series of divergent passages. There’s the baroque jam on the middle section, also called “Terrapin Station.” This then veers into the fusion jazz on “Terrapin Transit” and “At A Siding.” The tune then speeds up to capture the hyperactive sound of a moving train on “Terrapin Flyer,” which with its rattling bell percussion, is similar to “Caution (Do Not Step on the Tracks)” from Anthem of the Sun. The song ends with the a reprise of “Terrapin Station” complete with a bombastic orchestra and a choir calling out “Terrr-aa-peen” as if it were the finale to a grand opera. While the song is certainly long, it has enough variety that it does not feel tedious or overstretched, unlike so many of the band’s endless jams.

Robert Hunter claims he and Jerry Garcia wrote the lyrics and music separately on a single day in 1976. “When we met the next day, I showed him the words and he said, ‘I’ve got the music.’ They dovetailed perfectly and ‘Terrapin’ edged into this dimension,” Hunter said. Garcia’s biographer Blair Jackson dubbed the song, “a culmination of sorts for the Hunter-Garcia writing partnership — a place where the deep folk roots blossomed into a mythic dimension outside of time and space.” Garcia actually heavily edited the lyrics, but Hunter’s full version can be heard on his 1980 solo record Jack O’ Roses.

The band initially struggled to put the whole thing together. Describing the recording process in his memoir, Bill Kreutzmann writes, “After we’d been wrestling with it, unsuccessfully, in the studio, I came to the conclusion that part of the problem rested on Mickey and me. We hadn’t agreed on a precise arrangement, and a song like “Terrapin Station” needs a precise arrangement. Late that night, I went to Mickey’s apartment — we were all in the same basic apartment complex — and I told him that we were going to stay up and work on the song until we got it right. No more faking it. We sat down and mapped it out. … We went back into the studio, the next night, and got it right.”

When the tracks were completed in the spring of 1977 Olsen took the tapes to London where, along with arranger Paul Buckmaster, he recorded several orchestral sections to the piece. In the process, Olsen erased part of the drum track, replacing the section with strings, a decision that ultimately didn’t sit well with the Rhythm Devils. “Without telling anyone in the band, he erased Mickey’s part entirely and then hired a string section to fill out that passage instead. I was pissed off about it, but Mickey was deservedly outraged,” Kreutzmann said. Hart called it “one of the most disrespectful things that has even happened to me musically … He didn’t ask — he erased it off the master and replaced it with strings.” Olsen claims he was given authorization by Garcia and Weir, “I said, ‘Do I have to go through every member of the band?’ They said, ‘No we’ll take care of it.’ But I don’t think they ever told anybody.” Clearly, this was all done long before anyone gave any thought of releasing a rarities or alternate cuts album.

Despite the strength of the opening and closing tracks, the middle section of the album is more uneven. After “Estimated Prophet, Track 2 is the band’s discofied cover of Martha and the Vandellas “Dancin’ in the Street,” a song universally hated among Deadheads, critics and band historians. Then there’s “Passenger,” a hard rock track written by Phil Lesh. “The only reason I made up ‘Passenger’ was that I wanted the guitar players to play with a little raunch” Lesh said. The album also includes a cover of the old gospel/blues tune “Samson and Delilah,” canonized by the Reverend Gary Davis. In this version, the band gives it a funky dance feel with a much more agreeable groove than on “Dancin’.” While Weir takes the lead vocal responsibilities, Donna Godchaux’s voice has one of the song’s most definitive moments. In the opening line of the chorus her voice punctuates the song, “If I had my WAY,” taking it up several octaves in a manner that the band would rarely be able to replicate live, especially after her departure.

Perhaps the oddest song on the album is Ms. Godchaux’s lead vocal effort, the side A closer, “Sunrise.” Written in honor of the band’s manager Rex Jackson, who died in a car crash in 1976, the song is a sad, mournful ballad, with heavy orchestration (also recorded by Olsen in London), and is one of the band’s few forays into mainstream pop. In fact hearing the song today, it almost sounds like a lost James Bond theme song (what a strange trip that would have been). It’s one of those rare moments that demonstrates the power of Ms. Godchaux’s voice. Before joining the Dead with her husband Keith, she had been a crack session singer who had worked with the likes of Elvis and Percy Sledge. When listening to “Sunrise” I can’t help but think her vocal talents were mostly underutilized by the band.

Terrapin Station sold modestly well upon its release, eventually going gold in 1987 when “Touch of Grey” helped boost the group’s back catalogue album sales. Though the album failed to produce a radio hit, Davis claimed in his autobiography that he thought it was a strong record.

Despite the band’s conflicts with Olsen, the collaboration clearly strengthened the group’s sound. The Dead’s 1977 tour is still considered one of its finest. Famous dates include the near mythic performance at Cornell’s Barton Hall and a show played in front of 150,000 at Englishtown Raceway in New Jersey. Browne credits the strength of this tour to the band’s work with Olsen. “All the hours the Dead had logged in the studio with a chart-minded producer had transformed the band into a monstrously strong unit. … Whether in college gyms, theaters, or arenas, they’d rarely sounded so well oiled.” The pop charts would simply have to wait another decade.

Sources

Browne, David. So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. Da Capo Press, Boston, MA. 2015.

Davis, Clive and DeCurtis, Anthony. The Soundtrack of My Life. Simon & Schuster, New York. 2013.

Gans, Davis. Conversations with the Grateful Dead: The Grateful Dead Interview Book. Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA 2002.

Jackson, Blair. Garcia: An American Life. Reissue. Penguin Books. 2000

Kreutzmann, Bill and Eisen, Benjy. Deal: My Three Decades of Drumming, Dreams and Drugs with the Grateful Dead. St. Martin’s Press, New York. 2015.

Lesh, Phil. Searching for the Sound: My Life with the Grateful Dead. Little, Brown and Company, New York. 2005.

McNally, Dennis. A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead. Broadway Books, New York. 2002.

Trager, Oliver. The American Book of the Dead: The Definitive Grateful Dead Encyclopedia. Fireside, New York. 1997.

No comments:

Post a Comment