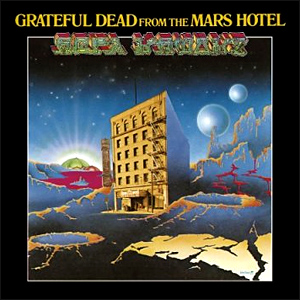

It seems fitting that there is no consensus on what the Grateful Dead’s seventh album is officially called. In some places it’s listed as Grateful Dead From the Mars Hotel, in others it’s From the Mars Hotel and often it’s cited as simply Mars Hotel. The record — named after the San Francisco dive that Jack Kerouac mentioned in his novel Big Sur — is awash in contradictions.

The album contains eight of the slickest, tightest studio recordings in the band’s catalogue. Yet, unlike its predecessor Wake of the Flood, which has a consistent, well-put-together feel, Mars Hotel is all over the place musically, making it difficult to listen to straight through. Even playing it on shuffle doesn’t throw off the rhythm of the album, because there isn’t one.

Mars Hotel was recorded at CBS Studios in San Francisco between March and April 1974 at a time when the city was in the midst of a crime wave that came to be known as the “Zebra” murders, a series of racially-motivated killings that had gone on for over a year. Drummer Bill Kreutzmann describes the scene in his memoir: “People were terrified to walk the streets at night. The [San Francisco Police Department] launched an unprecedented dragnet, as they racially profiled more than 500 ‘suspects’. I remember hearing sirens constantly wailing in the distance, as I’d cross the Golden Gate Bridge heading downtown to work.”

The group spent about a month rehearsing the songs before entering the studio and took a serious approach to recording. In So Many Roads, David Browne describes the sessions, “The loose knit atmosphere of the Sausalito sessions for Wake of the Flood was out, replaced with a more professional undertaking that began with an in-house engineer, Roy Segal, who had worked with fastidious record makers like Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel.” Segal’s long list of studio credits as a producer and engineer also includes Janis Joplin, Sly and the Family Stone, Johnny Winter and Billy Cobham, among many others.

As usual, band members were divided over the outcome. Jerry Garcia called it, “an excellent studio album,” but with the caveat, “the aesthetics of making a good studio album is that you don’t hear any mistakes. And when we make a record that doesn’t have any mistakes on it, it sounds fucking boring.” Phil Lesh barely mentions the album in his memoir, despite the fact that it contains one of his signature songs, “Unbroken Chain.” Kreutzmann said in his autobiography that he doesn’t even own a copy of the album, but concedes that it “turned out alright.”

The album opens with the hard-rockin’, Chuck Berry-esque “U.S. Blues.” Much has been written about Berry’s influence on the band, as they regularly played a number of his songs throughout their run, including “Johnny B. Goode,” “Around and Around” and “Promised Land.” Berry even opened for the Dead in 1967.

Like many of Berry’s songs, such as “Sweet Little Sixteen” and “Back in the U.S.A.,” “U.S. Blues” contains a pastiche of images and artifacts from American culture, tinged with a bit of irony.

I'm Uncle Sam, that's who I am; Been hidin' out in a rock and roll band.

Shake the hand that shook the hand of P.T. Barnum and Charlie Chan

The lyrics are tied together with the hook-laden chorus and Berry-style guitar solo.

Wave that flag, wave it wide and high.

Summertime done, come and gone, my, oh, my.

Whenever I hear it, I can’t help but think that some Republican politician will use it at one of their campaign rallies only to receive a strongly worded cease-and-desist order from the band’s management the next day. To that end, in The Grateful Dead FAQ, Tony Sclafani compared the song to Bruce Springsteen’s 1984 hit, “Born in the U.S.A.” “It’s a protest song that can also be interpreted as a celebration of the country because of a rousing chorus.”

The album shifts completely on the second track to the softer, harpsichord-driven “China Doll.” Robert Hunter wrote the lyrics after a friend’s attempted suicide, and originally dubbed it “The Suicide Song,” thus explaining the dark, haunting opening passage: “ A pistol shot at 5 o'clock/The bells of heaven ring.” Underneath the harpsichord and vocals, you can hear a searing guitar solo. The song is a jarring listen after the album’s upbeat, fast-paced opener.

The third track “Unbroken Chain” is one of the most interesting and unusual in the Dead’s catalogue. The song feels like a pocket symphony, with a number of different sections and movements. Sclafani called it “a feast for the ears, with swooshing synthesizer effects and a complicated mid-song jazz break.”

Written by Lesh, who had singing duties, with lyrics by Bobby Peterson, it differs in sound from much of the Dead’s material. I would often include it on mix tapes (back when I made such things) and would inevitably be asked the question: “is this a Dead tune?”

The lyrics touch on the big topics: religion, love, death, forgiveness, even football (“drop you for a loss”). The words “unbroken chain” are the connective glue that holds the song together. They are first sung in the opening line, with Donna Godchaux calling out, “Blue light rain,” to which Lesh replies, “Whoa, unbroken chain.” The phrase appears again later in the track after an extended, multi-directional jam, which Lesh ends by singing the words, “Lilac rain, unbroken chain.” The song then ends with the series:

Unbroken chain of sorrow and pearls

Unbroken chain of sky and sea

Unbroken chain of the western wind

Unbroken chain of you and me

Lesh seems to have a complicated relationship with the song. He is quoted in the American Book of the Dead, saying, “I gave up songwriting after Mars Hotel, because the results were disappointing. “Unbroken Chain’ could have been really something. Some people think it really is, but I wanted it to be what I wanted it to be.”

Yet, he would later call his autobiography Searching For the Sound after a passage from the lyrics, and in it he would call the song his “best.” It would remain unplayed in concert until 1995, when the band finally performed it 10 times, including during their final show at Soldier’s Field. Lesh credits his son Grahame for urging him to introduce it into the repertoire. “Grahame, after listening to the record version, was so enthusiastic about hearing it performed that I just couldn’t refuse — and lo and behold it came off so well that I was encouraged to continue slotting it into our sets.”

Hearing the crowd’s response when the group first performed the song at the Spectrum in Philadelphia on March 19, 1995, you can tell that most fans agreed with Lesh’s son. Garcia’s biographer and band historian Blair Jackson, called the song’s reintroduction a highlight of the group’s final year on tour. “It was ecstatically greeted each time, particularly by older Deadheads who’d worn out copies of the Mars Hotel album in the era before Dead bootleg tapes became widely available, when records were still the main medium for listening to the Dead.” The fact that they could take the song out of purgatory twenty years after its original recording and receive this kind of response speaks volumes about the strength of the original recording.

Lesh and Peterson had one other track on the album, the countrified “Pride of Cucamonga.” The song, also sung by Lesh, sounds like a lost track from the American Beauty/Workingman’s Dead era, and one can easily picture it being sung by Merle Haggard and/or George Jones.

The most interesting moment in the song occurs just before the bridge. For a second, it feels as though the band is going to speed the track up and take it into blues-rock territory. Then they pull back, and the song shifts into a pedal steel solo by John McPhee (Garcia is sometimes given credit). “Pride of Cucamonga” was never played live during the band’s original run but was included on Phil Lesh & Friends’ 2006 album Live at the Warfield. In that version, guitarists John Scofield and Larry Campbell take the interlude to its logical and most Dead-like conclusion with an extended jam.

If Mars Hotel’s opening track is an homage to the band’s rock and roll roots, then the fifth song, “Scarlet Begonias,” provides a preview of the Grateful Dead’s new direction on its subsequent albums. The song’s high-pitched keyboards and multi-layered, world-beat inspired funk came to define much of the band’s sound through the late 1970s. During the band’s legendary show at Cornell’s Barton Hall in 1977, they paired it with “Fire on the Mountain,” which would appear on Shakedown Street. The songs work well together because they’re nearly identical.

Just as the lyrics to “U.S. Blues” contain American imagery, “Scarlet Begonias” makes a number of references to Merry Ole England. Most notably there’s opening line, “As I was walking round Grosvenor Square,” which refers to a place in Mayfair. The song was based on a love affair lyricist Hunter had on the other side of the pond.

Of all the songs on the album, the second to last track, “Money, Money,” written by Bob Weir with lyrics by John Barlow is the least popular. It seems to be universally hated by fans, critics and band historians, primarily for its “sexist lyrics.” For example:

Lord made a lady out of Adam's rib,

Next thing you know, you got women's lib.

Lovely to look upon, Heaven to touch;

It's a real shame that they got to cost so much.

So the song is clearly no “Sugar Magnolia” or “Scarlet Begonias” in terms of romantic sentiment. But whenever I read these critiques I always think it odd that people dislike the song for being sexist. The band has plenty of songs in its catalogue that aren’t exactly P.C. towards members of the opposite sex. Fans, critics, et al., are also much more forgiving of track four, “Loose Lucy” where, to my knowledge, no such backlash exists despite the opening lines: ”Loose Lucy is my delight, she come runnin' and we ball all night.”

I believe the song has earned such a backlash because it’s the worst track on an otherwise solid album. Also, before CDs, fans had to endure it to get from “Pride of Cucamonga” to the album’s closer “Ship of Fools,” so they were stuck with it one way or another. I feel like that’s a good parable for the album itself. The band might not have not necessarily been happy with the outcome, but given its quality and the number of great songs, they had to account for its existence and popularity over time.

After all the different musical directions the Grateful Dead explores on Mars Hotel, the album’s final turn is a quiet one. It ends with the mournful ballad “Ship of Fools.” Many of the band’s chroniclers have labeled it as an allegory about the political climate in the U.S. surrounding the decline and fall of President Richard Nixon. Some push it even further, labeling it a parable for the state of the Grateful Dead itself as the band was nearing exhaustion and would take a break from the road soon after. Hunter’s lyrics are intentionally vague, forcing listeners to draw their own conclusions. The song ends with a sad, requiem-like guitar solo, which like many Grateful Dead studio tracks fades out a bit too soon. As unsettling as the album’s twists and turns can be, in the end, it still leaves you longing for a bit more.

Sources

Browne, David. So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. Da Capo Press, Boston MA. 2015

Dodd, David. The Complete Annotated Grateful Dead Lyrics: Fiftieth Anniversary Edition. Simon & Schuster. 2015

Kreutzmann, Bill and Eisen, Benjy. Deal: My Three Decades of Drumming, Dreams and Drugs with the Grateful Dead. St. Martin’s Press, New York. 2015.

Lesh, Phil. Searching for the Sound: My Life with the Grateful Dead. Little, Brown and Company, New York. 2005.

Richardson, Peter. No Simple Highway: A Cultural History of the Grateful Dead. St. Martin’s Press, New York. 2015

Sclafani, Tony. The Grateful Dead FAQ: All That’s Left To Know About The Greatest Jam Band In History. Backbeat Books, Milwaukee, WI. 2013.

Trager, Oliver. The American Book of the Dead: The Definitive Grateful Dead Encyclopedia. Fireside, New York. 1997.

McNally, Dennis. A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead. Broadway Books, New York. 2002.