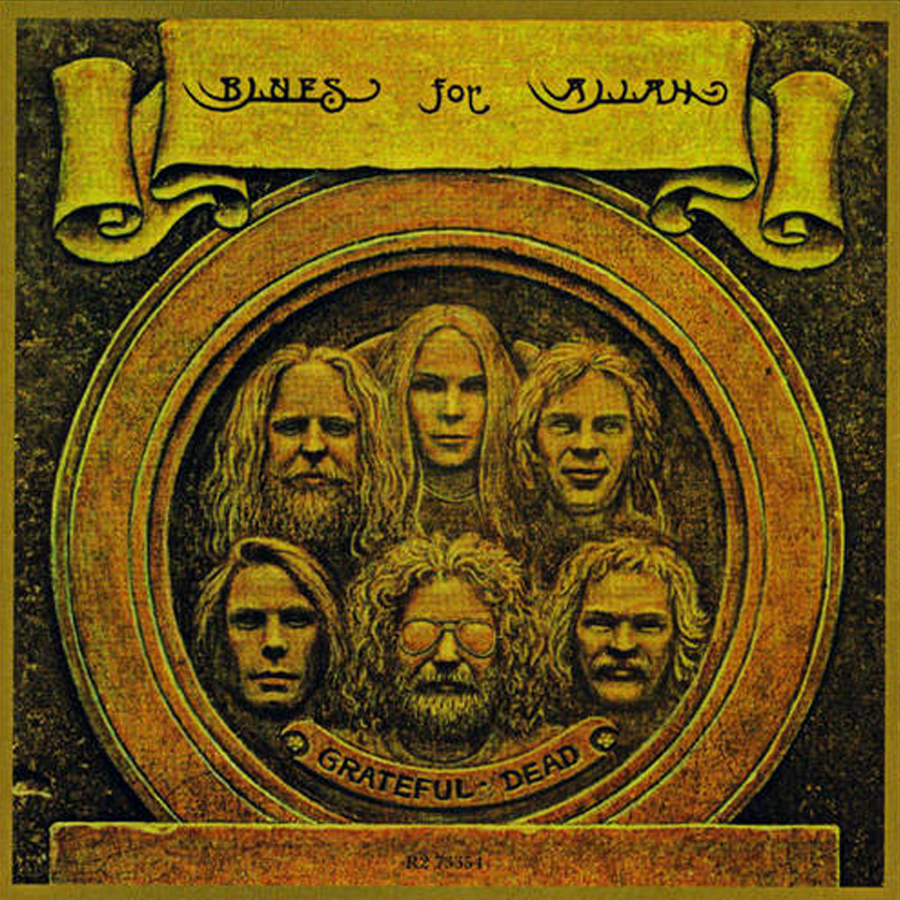

The Grateful Dead’s eighth studio album Blues For Allah would prove to be a transitional record for the band. With it, they entered a new phase, hinted at as far back as “Alligator” on 1968’s Anthem of the Sun but more fully explored with “Scarlet Begonias” on Mars Hotel. The album features a mix of 70s funk, hard-edged R&B, fusion jazz, world-beat rhythms and even a bit of the sound that came to define the decade, disco. This scattered musical buffet would characterize the sound on the band’s next two records, Terrapin Station and Shakedown Street.

“Anyone who thinks the Dead ‘went disco’ with Shakedown Street needs to take a closer listen to 1975’s Blues for Allah,” Tony Sclafani wrote in the Grateful Dead FAQS.

Blues for Allah also marked the return of prodigal drummer Mickey Hart who had left the band several years earlier after his father was arrested for stealing money from the group. His comeback would enable the band to push its sound palate beyond the basics of rock and country and meld together complex, polyrhythmic sounds that also blended elements of Caribbean and Latin music. Hart’s major contribution to the record, which is in nearly every history of the album, was his decision to bring crickets — not Buddy Holly’s backing band, but actual crickets — into the recording studio for the album’s extended title track.

The album is one of the jammiest in their catalog, second only to Anthem of the Sun in terms of experimentation. It was recorded in Bob Weir’s home studio in early 1975, while the band was on a touring hiatus following a series of “farewell” shows in late 1974.

The word “comfortable” comes up often in various histories of the band. “This forced intimacy (no isolation booths or baffles, there wasn’t room) really enhanced the process of developing the tunes,” Phil Lesh wrote in his memoir. “We had to play them like a band would onstage milking them for all the expressive content we could find.” The home-like atmosphere of the sessions also allowed the band to loosen up, which you can hear loud and clear in the open-ended feel of the record. “For the first time, the Grateful Dead went into a studio with no material and no notion of the next gig, a creative tabla rosa that would be unique in their recording history,” historian and publicist Dennis McNally wrote. “They laughed, they got crazy, they thoroughly enjoyed themselves.” Describing the process Jerry Garcia said, “We’d go into the studio, we’d jam for a while, and then if something nice turned up we’d say ‘Well, let’s preserve this little hunk and work with it, see if we can’t do something with it’.”

Not everyone thought the atmosphere was conducive to recording: drummer Bill Kreutzmann described the scene as being “too relaxed” and “too comfortable” and thought the music suffered as a result, despite the plethora of strong material. “We should’ve let the new tunes breathe a bit more before we recorded them, because they really deserved better.”

With this album in particular the band pushed the boundaries of improvisation in number of directions, leading to some classic songs, and some that were less so.

The album opens with the funky suite: “Help on the Way/Slipknot!/Franklin’s Tower.” With its slow-jam grooves I associate “Help …” with some of the harder-edged R&B songs of the era, like Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler),” Bobby “Blue” Bland’s “Ain’t No Love in the Heart of the City” and Bobby Womack’s “Across 110th Street.” With its chorus “Help on the way/I know only this/I've got you today/Don't fly away/'Cause I love what I love/And I want it that way,” the song might be describing a relationship but seems to hint at something fraught with chaos.

The suite shifts from “Help …” into “Slipknot!” an electric jazz instrumental jam, that would have been at home on some of the fusion jazz records of the era. The Dead had always flirted close to the edge of the fusion sound, especially with “Dark Star.” But the feel on this track is much funkier and looser, similar to tracks on the Mahavishnu Orchestra's The Inner Mounting Flame or Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters. The trio of songs ends with the hippie sing-a-long “Franklin’s Tower” with its memorable chorus, “Roll away the dew.”

The album continues on its fusion progression with another jazzy instrumental,“King Solomon’s Marbles.” Following this it shifts more into disco with “The Music Never Stopped.” The song was written hastily during the final stages of the recording process. According to McNally, Weir called his lyricist and writing partner John Barlow and played some of the melodies over the phone. Barlow worked all day on his ranch and came up with the lyrics, which he relayed back to Weir in the evening. The song itself is a duet between Weir and Donna Godchaux and the first studio track where she does more than sing backup.

After that comes “Crazy Fingers.” Though the song has a slow reggae vibe, it didn’t start out that way. Blair Jackson wrote, “Garcia said in his original setting the song was almost heavy metal, but by the time it reached the concert stage it had been transformed into a floating, lyrical, slow reggae tune that perfectly matched the feeling of the words.” The song sounds more like some of Jerry’s solo material, at the time the Jerry Garcia Band was performing a number of reggae covers in its live shows.

Though the album was recorded a whole two years before Fonzie made his proverbial water ski jump over a caged shark on Happy Days, Blues for Allah jumps a shark of its own after “Crazy Fingers.” When the album lands on the instrumental track “Sage and Spirit,” it sounds like it would be at home on any album of classical recordings. But that song feels like a down-home classic compared to the album’s truly weird title track, “Blues for Allah.” The 12-minute piece features extensive chanting, long meandering jams, and yes, Mickey Hart’s crickets. Garcia couldn’t really describe what was going on in the song. “That song was another totally experimental thing that I tried to do,” he said. “In terms of the melody and the phrasing and all, it was not of this world. It’s not in any key and it’s not in any time. And the line lengths are all different.”

At its best moments, the song serves as a prelude to the band’s extended “Space” jams in the 1980s and 90s. At its worst, with the chanting, well, historian David Browne summed it up best, saying the group sounded like “Marin County monks on an acid trip.” Personally, I think they sound a bit like these guys:

Even today, 41 years after the song was recorded it remains one of the most unlistenable in the band’s catalogue. The band only played it live a handful of times; sources vary as to how few: a mere 3, 5 or 6 times, depending on the Dead database.

With the jammy, meandering quality of the early songs and the outright bizzarro nature of the final two tracks, the album as a whole feels very uneven. Reactions to it by band members, historians and critics have been mixed over the years. Upon its release, Rolling Stone gave the band some backhanded praise for the effort saying, “the Grateful Dead have begun to awaken from the artistic coma they've been in since 1971. … They've also abandoned their tired philosophical stetsons and Old West daydreams in search of new frontiers. And though, on the basis of this record, one can't be totally convinced that it's better late than never, still, it's a good try.”

Jackson said, “If the record was lacking anything it was warmth and confidence that the band drew from playing the songs in front of people for awhile before recording them.” The only track to appear in a live show prior the band starting the recording process was “Slipknot!” Even that was only played once.

McNally blames the end result on the final push to bring the album out. Desperate for cash to support their fledgling label the band had signed a deal with United Artists to help with distribution. He notes that after several months of jamming in the studio the band was given a tight deadline for the final product. “As usual, the Dead managed to shoot themselves in the foot. They’d put together a wonderful set of material under ideal and relaxed circumstances.” But once the deadline came on, “They slammed through the final recording process in two or three weeks.”

Kreutzmann — who in his memoir is mostly derisive regarding the albums and the recording process in general — concedes that the music on the record is really good, “To this day, I still really love some of those songs.” But with an interesting addendum. The album itself was released on September 1, 1975. A few weeks before on August 13, the band played an invitation-only concert at the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco, where they performed every track from the album (though not in order). “Maybe the live run-through of the album should’ve been the album itself,” he wrote.

The band ultimately did release a live recording of the show in 1991 under the name One from the Vault. Listening to the albums side by side, it’s clear Kreutzmann is right. Even the best moments on the studio tracks play out much better in a live setting than in the studio, with more energy. The title track itself even fares a bit better, especially with the live crickets, who come through loud and clear on the concert recording. In the end, the chanting still dooms the song. Some things are better off left in the past.

Blues for Allah marked the end of another era for the band. It would be the last studio album they would put out on their own label. Shortly thereafter they would sign on with Clive Davis’ newly created Arista Records. Still, the band’s sonic direction had been firmly established and with a new label they would attain some brilliant heights and frustrating lows.

Sources

Browne, David. So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead. Da Capo Press, Boston, MA. 2015

Jackson, Blair. Garcia: An American Life. Reissue. Penguin Books. 2000

Kreutzmann, Bill and Eisen, Benjy. Deal: My Three Decades of Drumming, Dreams and Drugs with the Grateful Dead. St. Martin’s Press, New York. 2015.

Lesh, Phil. Searching for the Sound: My Life with the Grateful Dead. Little, Brown and Company, New York. 2005.

Sclafani, Tony. The Grateful Dead FAQ: All That’s Left To Know About The Greatest Jam Band In History. Backbeat Books, Milwaukee, WI. 2013.

Trager, Oliver. The American Book of the Dead: The Definitive Grateful Dead Encyclopedia. Fireside, New York. 1997.

McNally, Dennis. A Long Strange Trip: The Inside History of the Grateful Dead. Broadway Books, New York. 2002.